Around the time that Dustin Allen, a soft-spoken electrical engineer, turned 27, he noticed a small red spot on his right temple. He thought it was nothing, maybe an acne scar. But it didn’t fade away. In fact, it kept getting darker, and he started to see splotches of dark brown popping up inside it, too. He asked his primary-care physician if he should be concerned. “She said it just looked like sun damage and they typically don’t worry about that until it gets to about nine millimeters,” he says. His father had had melanoma, though, so he knew he was at higher risk for this most dangerous form of skin cancer—having a first-degree relative with it can push up your odds by 50 percent. And with his red hair and freckle-prone complexion, another risk factor, he couldn’t shake the bad feeling he had about that spot.

Allen tried to see a dermatologist to get a second opinion, but finding one where he lives in Texas—one who took his health insurance and had an appointment slot available—wasn’t easy, so he put it off until he had better insurance. When he finally got to see a dermatologist—five years later—the doctor initially said it was sun damage, but Allen pushed for a biopsy. Two weeks later, the doctor’s number showed up on his caller ID, and Allen knew the news wasn’t good. Sure enough, it was melanoma. “I wouldn’t say I anticipated it, but I wasn’t completely surprised,” he says. Luckily, it was still at an early stage, and within weeks he had surgery to remove the cancer. He was 32 years old. Many guys aren’t so lucky. Sometimes the time between diagnosis and a melanoma becoming fatal can be as short as a few months.

“Of the things that keep dermatologists up at night, melanoma is at the top of that list,” says Jonathan Ungar, M.D., medical director of the new Kimberly and Eric J. Waldman Melanoma and Skin Cancer Center at Mount Sinai in New York City. The fifth most common cancer for men and among the top three for young adults, it’s been on the rise.

We tend to think of melanoma as an older person’s problem, but the stats for young men are disturbing. Head and neck melanoma jumped 51 percent from 1995 to 2014 (the most recent years for which data is available), especially in non-Hispanic white men aged 15 to 39. And research published in JAMA Dermatology found that guys in that demographic, like Allen, make up a disproportionate number of melanoma-related deaths—more than 60 percent. You read that right: Of all the people who die from this, nearly two thirds are young guys. And they’re 55 percent more likely to die from melanoma than women in the same age group are.

Doctors are furiously trying to figure out why. Melanoma can be incredibly aggressive, and because young men don’t think it can happen to them and they don’t know the signs, they often don’t catch it when it’s most treatable. This form of cancer is caused by mutations in melanocytes, the skin cells that create pigment, and what makes melanoma so insidious is that “melanocytes are everywhere [on our bodies] and have these little wiry connections through the skin,” says dermatologist and leading skin-cancer expert Orit Markowitz, M.D. Once mutation begins, it can spread across this network extremely quickly. If tumor cells reach the bloodstream, which is a risk at all stages, they can be swiftly transported to other parts of the body, such as the lymph nodes, like cars merging onto a freeway. But knowing your risks and what to do about them could help turn around the scary statistics.

Preventing melanoma isn’t just about sun care

It would be easy to say that sunlight and ultraviolet radiation cause melanoma, because they generally do. And your risk goes up if a first-degree relative (like your mother or father) had melanoma or possibly other cancers, like breast or prostate. But that doesn’t explain why melanoma is so much more aggressive and, in many cases, more deadly in men than in women, or why it’s hitting younger guys in particular. Doctors have some theories, thinking the increase in risk could be biological, social, or maybe both.

One potential explanation is the classic idea that men might be putting themselves in harm’s way. Melanomas in men tend to be on the torso and back—spots that are exposed to the sun when guys take off their shirts to play basketball, mow the lawn, or walk on the beach. Deny that you’re lax about sun protection all you want, but the tumors tell the truth: Melanomas found in men usually have more mutations caused by UV radiation, notes Dr. Markowitz, as opposed to mutations caused by family history.

But more intriguing is the idea that men could be biologically more susceptible to melanoma. Sex hormones may play a role in how quickly it spreads, though exactly how is unclear—some experts think testosterone could spur melanomas to grow faster; others suggest estrogen could help protect skin against them. Women’s bodies may just have different ways to control these cancer cells, though what those ways could be is still being studied, says Eleni Linos, M.D., Dr.P.H., a dermatologist and epidemiologist at Stanford University.

But why it’s hitting younger guys is still a head-scratcher. Some doctors point to tanning-bed use—even a single session raises the odds of getting melanoma by up to 70 percent, says Mona Mofid, M.D., medical director of the American Melanoma Foundation. But that’s not so germane, since men aren’t the beds’ primary users.

Another reason could be that young guys don’t even have melanoma on their radar. Certainly 40-year-old Jonathan Benassaya didn’t. Growing up in the French West Indies, “we all knew that the sun wasn’t good for our skin, but to be honest, I didn’t pay much attention—I was surfing every day,” he says. He didn’t know anything about melanoma until he was diagnosed with it at age 40, after tagging along with his wife to a dermatologist appointment and asking for a skin check, too. The doctor noticed a mole on his nose. It had recently appeared, and Benassaya didn’t think it was anything. But she did. A few weeks later, the biopsy results came back: stage 1b melanoma—a large spot that is, fortunately, unlikely to spread. Like Benassaya, many men don’t know their risk factors and, as a result, don’t protect themselves.

Other contributors to the cancer epidemic

As with so many health problems, there are also social issues like access and inequality at play, experts suggest, pushing up the numbers for all men.

Access to a dermatologist isn’t a given. Even if every man in the United States suddenly tried to book a skin check, it wouldn’t end the melanoma epidemic. The country is riddled with “derm deserts”—areas where there isn’t a single dermatologist for miles. Men are less likely to see a dermatologist in general, and if getting an appointment when it’s needed isn’t possible—or takes too long—it keeps even more men away. Telemedicine has helped the situation some, but it can’t compete with an in-person appointment for diagnosing melanoma accurately. And because melanoma is such an aggressive cancer, the longer you wait to get it checked, the more likely it is to be fatal.

While the default “wear sunscreen” messaging around melanoma prevention is important, it can be harmfully reductive for some groups. Non-Hispanic white men are 25 to 35 times as likely to develop skin cancer as Black men, but people of color face heightened risk for a rare but more pernicious form. And this type of melanoma is not associated with sun exposure, according to a 2005 study from Brown University researchers. Acral lentiginous melanoma, found on the palms and the soles of the feet (and what Bob Marley famously died from), is “fast growing and hard to detect,” says Ade Adamson, M.D., an assistant professor in the Department of Internal Medicine at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin. And it’s more lethal than the more common types. Though it doesn’t affect more Black people than people of other groups, a larger proportion (around 36 percent) of melanomas diagnosed in Black people are acral. It’s possible that this kind of melanoma has some sort of genetic factor. But there are still many unanswered questions about it, which is why there’s a need to invest in more studies that look at how and why Black people are disproportionately hit with this type.

How to reduce your melanoma risk

Until scientists determine what’s causing the rise, your best melanoma-prevention tool is you. That means: Use sun protection, know your family history, and do your own skin checks. You also need to get a professional skin exam at least once a year. Here’s why:

When it comes to melanoma, nothing beats early detection. “When we catch it when it’s not spread at all, the five-year survival rate is 98 percent,” says Dr. Ungar. “Once it becomes more metastatic, that drops dramatically down to 25 percent.”

Though melanomas are often visible in the form of dark spots and moles, some are not. For instance, amelanotic melanoma produces light-colored spots, making it harder to detect, says Dr. Markowitz. Todd Pobiner, a patient of hers, had been going to the dermatologist his whole life—he knew he was at high risk because of his fair complexion and his propensity for moles at a young age. He was diagnosed with his first melanoma during a routine skin check at 25 and has had five or six more removed since. “I have scars all over my back,” he says. While the recommendation for most people is to get a skin check every year, he’s at such high risk that he gets one every three months. It was during one of them that a small pink bump on his shin—which didn’t look like anything—turned out to be amelanotic melanoma. “I wouldn’t have thought twice about the thing and it turned out to be one of the most deadly forms of skin cancer,” says Pobiner, now 42. “I might not be here if it wasn’t picked up. Three or six months could have made the difference.”

In the future, guys like Pobiner might get their own dermatoscopes, the tool dermatologists use to identify melanomas and other skin cancers. In the age of telemedicine, Dr. Markowitz and other physicians have been schooling patients in dermatoscope smartphone attachments (she recommends the DermLite HUD Home Dermatoscope, from $ 100), which take high-resolution pictures they can email to their doctors for better-quality at-home monitoring (though patients still have to go for an in-person check if something looks suspicious). And derms might not have to take as many biopsies, which leave patients like Pobiner with scars everywhere, thanks to a laser-imaging system called reflectance confocal microscopy. Used at some large medical centers now, it’s able to painlessly photograph slightly below the skin’s surface on the near-cellular level. “It allows us to make diagnoses or risk stratification without a biopsy,” says Dr. Ungar. Since it’s noninvasive, doctors can even examine the same spot multiple times without damaging the skin.

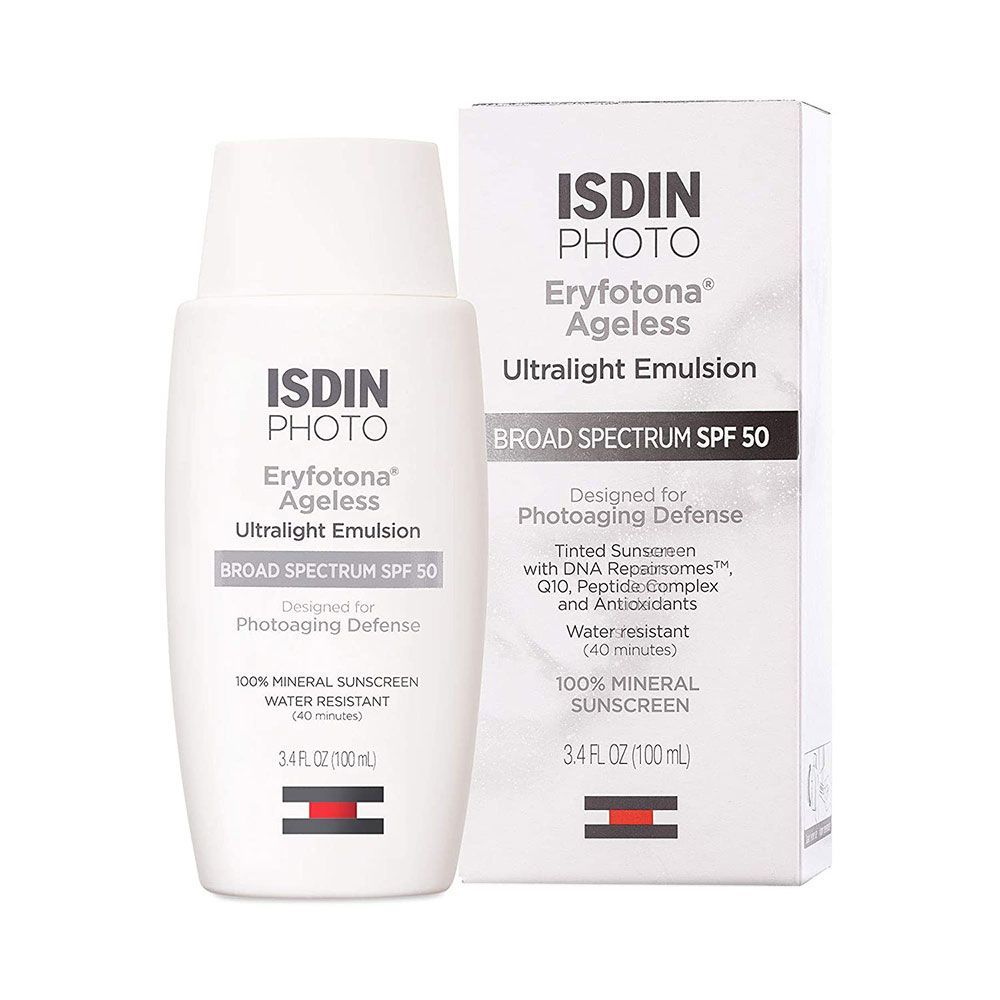

Luckily, even though he waited five years to get that red spot diagnosed, Dustin Allen was still able to have the melanoma surgically removed—many people are not. For more invasive melanomas, new treatments such as immunotherapy have changed the game. Since then, Allen has made some changes of his own, including a promise to himself to “never get another sunburn.” The days of leaving the house without sunscreen or a hat, as he did in his early 20s, are over. One melanoma was enough for him to learn his lesson, and there’s no going back, he says—if not for himself, then for the thousands of young men who weren’t so lucky.